Sun Power: The Global Solution

for the Coming Energy Crisis – Chapter 4 for the Coming Energy Crisis – Chapter 4

Sun Power

by Ralph Nansen

Copyright 1995 by Ralph Nansen, reproduced with permission

Chapter 4: The Great Energy Crisis

In 1973 the United States was at the peak of its economic development. It was the highest creditor nation, it had the highest per-capita gross domestic product, and real income for the average worker was at its maximum. Then Saudi Arabia led the Arab countries and other OPEC nations in the 1973-74 oil embargo. Our comfortable, energy-rich world was suddenly powerless. We waited in gas lines, reviling the oil companies. We cursed the Arabs and demanded that the government “do something.” It was a dramatic start to the current energy crisis, which has now stretched over two decades.

We believed when it started that it was a true crisis, and the reaction was typical of many crisis periods. There was a great deal of thrashing around in all directions looking for a way to end it. There were attempts to place blame and point fingers. Some people were demanding that we send in the army to take the oil from the Middle East by force, thinking “we have a right to it.” It was not a pleasant time, and our response as a people was not one of our finest hours.

It was a crisis that was inevitable—the only question was when and how it would occur. From the moment in 1901 when Spindletop brought the promise of vast quantities of cheap oil to the United States, our economy had been built on the use of energy to expand our productivity and enhance our daily lives. During the early years of the century the US was the largest oil producer in the world. Production supplied all the US demand, and oil was exported to other nations. We did not heed the first warning sign in 1948, when the United States changed from an oil-exporting nation to a net oil-importing nation. The oil reserves, which were so large at first, were proving to be finite in nature and we were using them at a prodigious rate.

When we first began to import oil nobody was concerned. Most of it came from the Middle East and was supplied by American-owned companies at a cost of less than $2 a barrel. The next warning sign came in 1951 when Mohammad Mossadeq, the leader of the Nationalist Front in Iran, gained control and became prime minister. Upon assuming office, he nationalized Iran’s oil. When the US realized that Mossadeq and Iran were capable of exploiting the oil resources without US participation they turned to the Shah, the leader of the antinationalist forces in Iran. With direct CIA aid, a military coup ousted the nationalists and restored the Shah to power in August of 1953, thus attaining a more favorable oil policy. The seeds of trouble had been planted, however.

Ten years later in March of 1963 the next big milestone was reached as the Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO) agreed to relinquish 250,000 square miles of oil concessions back to Saudi Arabia. This was followed by the nationalization of oil in Iraq in 1972. The stage was now set for the crisis to begin.

At the beginning, the most staggering of all effects, besides the shortage of gasoline, was the rising cost of petroleum products. In 1973, gasoline could be bought for 35 cents per gallon, and a station attendant checked the oil and cleaned the windshield. A few years later, $1.40 per gallon was common, and we filled the tank and washed the windows ourselves. The cost of heating oil took an even deeper bite as we were forced to lower the thermostats in our homes and make sacrifices in other essential areas.

During the 1970s the process of adjusting to the higher real costs of living meant that we could not buy or do as many things as we once could. This resulted in reduced sales of goods and services. Business slumped and people lost their jobs, so now there were fewer people who could buy goods and services. This cycle, once started by the driving force of high-cost energy, continued until a new lower level of balance was achieved.

The economic recession that resulted impacted most of the world. Unemployment was very high. The banking system was balancing on the brink of disaster because of massive loans to third-world nations. Many of these loans were made to help compensate for the high cost of energy. Some were made to oil-producing nations to provide for industrial expansion. Even many of the oil-producing nations were in serious economic trouble as the demand for oil decreased significantly due to its high cost. They had borrowed heavily on the promise of future riches, believing their “black gold” could be sold at any price. However, with the demand reduced, the OPEC nations could not discipline themselves into reducing production enough to sustain the unrealistically high price, and it fell.

The price demanded by the Middle East oil-producing nations had nothing to do with their cost of producing the oil. When the embargo started in 1973, the cost of producing oil in the Middle East was approximately 25 cents per barrel. The price was raised to over $30 a barrel. We all breathed a sigh of relief when the price fell, but it never returned to its original level.

Meanwhile, the economy struggled back to reasonable health, but our world had changed. We switched to smaller cars, many built by the Japanese. We recognized the need for greater energy efficiency. Industries that were energy inefficient were in serious financial trouble. We were more aware of the finite supply of available oil and how difficult it was to switch to other sources. Very few new oil reserves had been found. No new large-scale energy sources had emerged to replace our dependence on oil. The debt of third-world nations was out of hand. Balances in international economics had changed. Japan had emerged as a dominant industrial nation because they were more prepared to absorb the energy cost increases than the US. Lacking their own resources, the Japanese have had to import energy from the start of modern times—their economy was already geared to very high energy efficiency.

Easing Crisis Brings a False Sense of Security

By the time the decade of the 70s was over, the initiatives made by the US to increase energy efficiency were starting to pay off. The reduced demand for foreign oil helped stabilize the price. Most people thought the crisis was over and forgot about doing anything about it. As the 1980s progressed the usage began to grow again—we had eliminated inefficiencies, but the population continued to expand.

Then in 1990 Iraq seized Kuwait and put a strangle-hold on the oil-hungry world. We were held hostage by a single madman. The price of oil once more jumped sky high. The US lead the combined military forces of many nations to free Kuwait. The banner under which the forces fought was “civil liberties of Kuwait,” but we had really gone to war over oil. Fortunately, it was a war that had the total commitment of the United States and the support of most of the rest of the world. Its limited objectives were quickly and decisively achieved. The price of oil dropped again, but not as low as it had been before the war with Iraq. The US was left with one of the longest recessions since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

We were not alone in the recession. Most of the other industrialized countries were also involved. The European Community, New Zealand, and Australia are all suffering from seriously depressed economies and unemployment. In Japan, where economic growth had been nearly continuous for decades, real estate values dropped dramatically, the stock market tumbled, and their vaunted manufacturing industries floundered—this time, they did not hold the energy efficiency edge.

Japan’s story during the oil crisis of the 1970s is an interesting one to review because it was during that decade that Japan emerged as one of the economic and industrial giants. Theories about why they were so successful have been analyzed and discussed for years, focusing on factors such as their management systems, their dedication to quality, government/industry partnership, emphasis on research, and the willingness of the work force to work long hours at low wages. All of these factors undoubtedly did contribute to their success, but one feature that has not been analyzed is the impact of world energy costs and how they opened the door to success for Japan.

Japan has practically no energy resources. They have had to import essentially all of their energy used during this century. Out of necessity, they built their industries around highly energy efficient approaches. When the cost of energy suddenly rose, Japan had to pay the same higher prices as did the other oil-importing nations, but Japan’s industry was impacted less because they were already using the newest and most energy efficient systems available. Their entire automobile industry was based on small, fuel-efficient cars.

The United States on the other hand was caught totally unprepared. We had recently extracted ourselves from the quagmire of Vietnam. The scandal of Watergate had drained the national confidence even further. Our industries had not modernized to take advantage of more energy efficient processes because there was no apparent need—oil was still cheap. So when the OPEC oil embargo came, our industry was cut off at the pockets. American steel companies could no longer effectively compete in the world market because of their high manufacturing costs due mainly to obsolete, energy-intensive processes. The American automobile industry was still building big, low-mileage muscle cars that very few people could afford to drive anymore. The rest of American industry had similar, if less critical, problems facing them with the increases in energy costs.

In this environment Japan was ready to exploit its advantage in the world marketplace. It took the United States automobile industry nearly ten years to turn around and start to be competitive in the fuel-efficient car market. The steel industry never did effectively recover. During this period of explosive growth, Japanese industry became dominant in much of the world market. Their entire manufacturing industry benefited because of the great influx of capital that flowed into their country.

During that period, the US industry struggled to adjust to the altered energy price pressures and gradually increased their efficiency. As a result the situation has changed in the ensuing years, and the recent energy price increases have affected most of the industrial countries in a similar fashion. Japan no longer has a big advantage, and they are suffering a recession and wondering what is happening to them.

Meanwhile another frightening milestone was reached in the US in 1992. For the first time in our history the number of jobs in the manufacturing industries fell below the number of jobs in government services. There were 18,300,000 workers in the manufacturing industries, which is a primary part of our society that enhances the total wealth of the country. That number is now exceeded by the 18,400,000 people who are working in government services at all levels. This segment of our society simply stirs the wealth around and makes no contribution of its own. It is another very serious sign of the deterioration of our economy.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the removal of price controls in 1992, the people of Russia have faced price increases that are far beyond their ability to pay as they struggle to make the transition to a market economy. Their country is essentially bankrupt, and they are looking for help from the West. Many of their scientists and engineers look forward to a jobless future as their efforts to develop machines of war are no longer needed. In addition, it appears that Russia will soon become an oil importer instead of an exporter.

The OPEC nations are gathering their strength again and plan new production limits and price increases. It is only a question of time until the next phase of the energy crisis occurs. It could be very damaging indeed. Conservation efforts have already forced the removal of most of our energy inefficiencies. The next time, we will have to reduce our standard of living dramatically and suffer the resulting economic penalties.

Very little new oil has been found over the last twenty years, and very few new energy sources have been brought on line to contribute to our energy future. In the meantime, most of the nations of the world are in economic recessions. The US is doing little as a nation to solve our energy crisis—aside from closing our eyes to it and planning ways to increase our conservation efforts. Each day we delay brings the day of reckoning one day nearer.

Inflation — Energy Costs in the Driver’s Seat

Economists talk of controlling the money supply in order to control inflation. This idea is undoubtedly partially correct, but other factors can also have significant effects. As the real cost of energy rises higher in relation to other costs, it then affects the cost of everything we do. It not only influences the cost of fuel for our cars and furnaces, but also the cost of food and other products we buy.

Looking at our food chain illustrates this point. Our food comes from farms operated by less than 4% of our population. This is made possible by highly mechanized operations that use energy to replace human labor. Many farms are irrigated by water sprinkler systems that use electric power to pump the water. The water flows through pipes made of aluminum manufactured with the aid of electricity. The fields are fertilized with petroleum-based products that require additional energy to process. Once the food is grown and harvested, it has to be transported to market in a system that uses energy to power either trucks or trains. Often the food must be refrigerated to keep it fresh for our tables—another use of fuel.

As you can see, an increase in energy cost affects the cost of food at every step. After increasing efficiency, any further effort to reduce energy will result in decreased productivity, which increases cost. The end result is that the farmers and the processors have no choice but to pass the cost on to us if they are to stay in business. This is one of the hard-core foundations of inflation.

This same sequence of events occurs with every product we use. It often starts with the mining of ore, which is the basis of many of our raw materials. The machines to extract the ore from the ground, whether in deep shaft mines or surface strip-mines, are operated by energy. Next the ore must be processed into raw materials such as steel, glass, copper, and aluminum. The processing normally requires high temperatures, which must be provided by some type of energy source. This processed material is then formed into a useful product—requiring more energy to shape and form. Then comes the finishing—baked enamel, ceramic coatings, tempered glass, or polished brass—all requiring energy. Finally, these products have to be transported to the marketplace—often to an intermediary destination before finally being transported to their place of use. Even though we are now recycling many of these raw materials, much of the cycle must be repeated again.

It is interesting to note that one fourth to one half of the operational cost of most commercial transportation systems is in fuel costs. Therefore, any change in the cost of energy has a large direct impact. Once a product reaches the marketplace—whether in the small corner grocery store or at the mall—it is displayed and stored in heated or refrigerated areas requiring energy. Then, of course, it has to be transported by the consumer to its final place of use, and when its usefulness has ended, the remains have to be transported either to the landfill or the recycling plant.

In many of the third-world nations I have visited, the shop owners cannot afford the cost of lighting or heating their shops. They only turn on the lights if you are going to buy something or, as is often the case, leave the lights off and just let you struggle to find what you want in the dim light seeping through an open door.

During the dramatic energy price increases of the 70s our country experienced serious inflation driven by energy costs. We will experience that again as the crisis progresses and energy costs surge. Will we be like the third-world shop owners and sit in our dark and cold buildings wondering what went wrong?

Communication Sharpens World Energy Demand

One of the technological developments that has become an integral part of our lives is the dramatic expansion of international communications. Its impact on the people of the world is very far reaching. Today, news is transmitted in real-time throughout the world. Televisions and VCRs have provided nearly everyone in the world an insight into what is going on in other places and countries.

Of particular importance is the display of the high standard of living achieved by industrialized free nations. One of the reasons for the failure of communism can be attributed to this opening in communications. People of the former communist countries were able to see how the people in developed democracies lived and began to ask, “What is wrong with our system; why can’t we have those things, too?” As these countries evolve into market economies, their standards of living will rise and the demand for energy will increase.

The same expansion of communications has filtered into the underdeveloped nations and exposed their people to new ideas. As I visited many underdeveloped countries scattered across the Pacific Ocean and came to know the people, I found that they all yearn for the things they have seen in the media. Never underestimate the far-reaching power of communication. While they appear to live simple, idyllic lives in their tropical island paradise, in reality their existence is at the subsistence level in most cases. When they are exposed to what they do not have, they become restless. People are the same everywhere, regardless of who they are or where they live. They want to improve their situation in life. Increased exposure to how it could be will bring an ever-increasing demand for development, which in turn is going to expand the need for energy to make it possible.

The Waning Years of the Third Era

We are looking into a future that has a growing world demand for energy. Demands from the newly free, former communist countries. Demands from the underdeveloped nations seeking their share. Pressure from expanding world populations, and the always present desire to improve our own standard of living in the US.

Since the start of the energy crisis in 1973 when the United States was at its economic peak, it has gone from the largest creditor nation to the largest debtor, now owing $1 trillion to foreign countries. United States manufacturers lost domestic market share in all 26 basic industries. Real income for the average American worker has dropped 8% and the per-capita gross domestic product has gone from being the highest to being the 10th highest. The national debt has ballooned to $5 trillion and is growing at the rate of half a billion dollars per day.

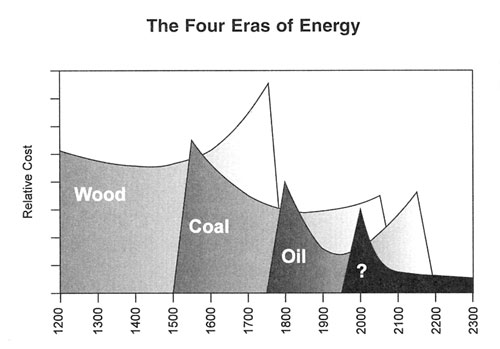

We are experiencing many similarities to the crisis that England faced when they were running out of wood. This time we are witnessing the beginning of the end of the third era of energy—the Era of Oil. As it was after the end of the Eras of Wood and Coal—wood and coal still exist as fuels today—the same will be true of oil, and it will be used far into the future. However, its days as the major world energy source and price setter are numbered.

The situation is even more serious than just the future of oil. In a paper presented in Dallas at the 16th Annual North American Conference, United States Association for Energy Economics and International Association for Energy Economics, in November of 1994, Richard C. Duncan revealed a startling analysis. His paper reviewed the resource predictions made by the eminent geologist and geophysicist M. King Hubbert over the last forty years. He explored the accuracy of Hubbert’s predictions on oil and natural gas compared to actual experience and concluded that Hubbert’s 1956 predictions for world oil and gas production are correct. Duncan’s further analysis of the data projects that world oil production peaked in 1984 and world gas production peaked in 1990. Duncan’s computed analysis based on historical data through 1993 places the peak of world coal production in 2007 compared to Hubbert’s projection of 2156. The difference is that Duncan believes that Hubbert’s prediction is erroneously based on the amount of coal in the earth, not on the amount that is practical to extract, which is only one tenth of the coal in the ground. If this is true then the world’s fossil fuel energy production will peak in 1994 and we are already beyond the point of no return for a smooth transition to a new energy source. To quote Richard C. Duncan, “This means that the world industrial civilization based on fossil fuels is now in irreversible decline. There is neither the time nor the energy, primary energy, to make a smooth transition to a high, or even a ‘sufficiency,’ steady-state.”

According to Cambridge Energy Research Associates, the emerging economies in Asia are escalating their demand for oil at a rate that will outstrip North America in energy consumption by 1999, while consumption in the US, Europe, and Japan has crept back to its highest level since 1979. Daniel Yergin, president of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, predicts that worldwide daily demand will rise by 11 million barrels over the next decade, an amount equivalent to the combined daily production of OPEC. Yergin warns: “There will almost certainly be at least one major energy surprise before the decade is out.”

The crisis that started with a traumatic oil embargo is now in full swing, but everyone thinks it is over because oil prices are low at the moment. It does not change the facts of what is happening. How long we wait to find a replacement is up to us. We can simply accept the situation as it is and hope something happens as our comfortable world disintegrates around us, or we can aggressively develop a new nondepletable, low-cost, environmentally clean energy source—a global solution for the coming energy crisis.