|

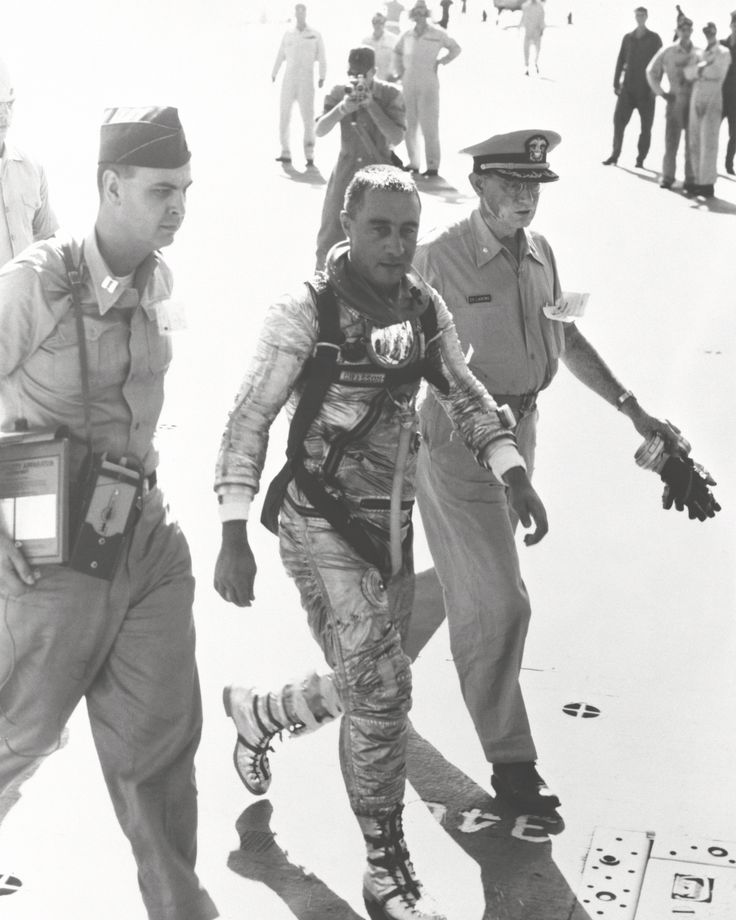

| Astronaut Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom is inserted into his Liberty Bell 7 capsule on the morning of July 21, 1961. He would soon be embroiled in a controversy that lingers to this day. Photo Credit: NASA |

In this installment of “Space Myths Busted,” I’ll tackle a myth that somehow still persists to this day despite many attempts to debunk it: On July 21, 1961, shortly after splashdown, a panicked Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom blew the hatch on his Liberty Bell 7 Mercury capsule shortly after an otherwise successful suborbital spaceflight. A clearly freaked-out Grissom then commenced to flail around in the water prior to being picked up by rescue helicopters. Read more after the jump…

The 1983 film The Right Stuff, canon among many space buffs,depicted Grissom in this exact situation. While the movie isn’t terrible, it’s more of a history of “moods” than what actually took place during the Mercury program, and its portrayal of Grissom is one of its biggest failings. By the time the movie was released, Grissom had conveniently been dead for over 15 years, leaving him essentially voiceless. So here’s what really happened during the Liberty Bell 7 recovery.

The book Into That Silent Sea by Francis French and Colin Burgess tells the story of Liberty Bell 7’s recovery in detail, beginning well before splashdown. While Grissom’s spacecraft floated under a ring-sail parachute toward the Atlantic Ocean, the astronaut – the second U.S. person to fly in space – began preparing for splashdown. A top-notch engineer and pilot, Grissom was hardly an acolyte, and had been training for this spaceflight since his astronaut selection in 1959.

Notably, this capsule possessed an explosive-actuated hatch, unlike the latch-operated hatch on the previous Mercury flight (Alan Shepard’s suborbital Freedom 7 mission, which had occurred in May 1961). The book explained how this hatch design was meant to work: “A percussion-activated, explosive primer cord surrounded the new hatch, and the astronaut had to activate a switch in order to arm the mechanism. When he was ready for recovery the astronaut would place the switch in the armed position, and a recovery loop on top on the capsule became the trigger. When the recovery helicopter’s hoisting cable was hooked onto the loop, the pressure created by lifting the capsule fired the mechanism and blew the hatch off.” Ironically, this hatch was designed for easy access, in case an astronaut was in trouble.

Before Liberty Bell 7 hit the water, Grissom was already hard at work, focusing on recovery. The book continued, “He reported opening his faceplate and then had problems inserting one of the door pins that held the hatch to the side of the capsule, a procedure designed to prevent the entire hatch from accidentally detonating outward when he began his exit from the spacecraft.” It was noted in the book that this step did not in any way contribute to what would soon occur. Liberty Bell 7 splashed down after a nearly picture-perfect mission at 7:36 a.m., some fifteen minutes after liftoff.

|

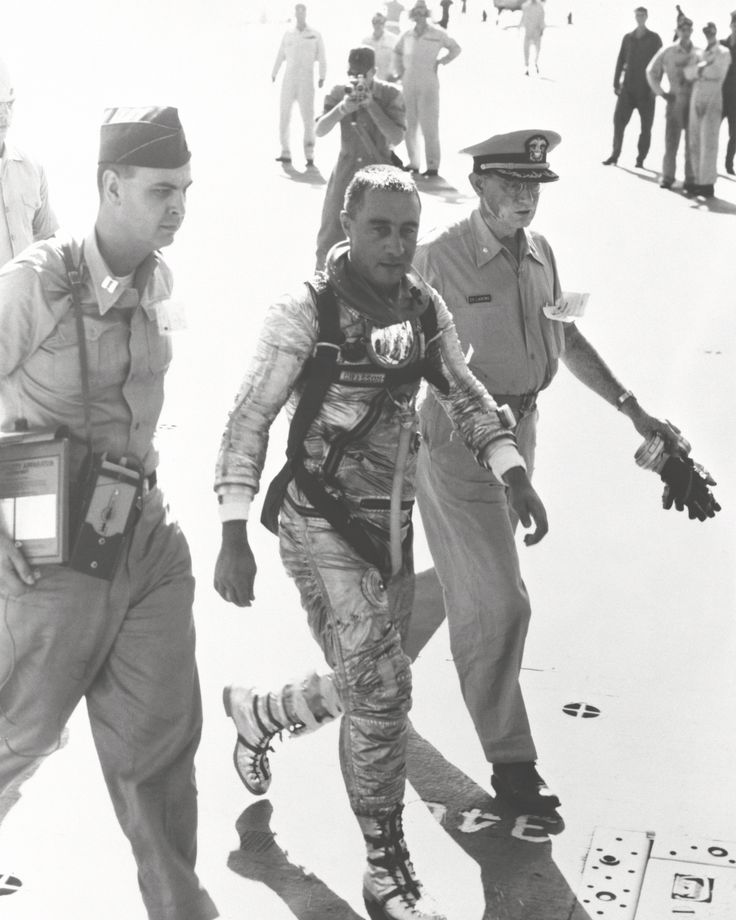

| An exhausted but safe Grissom on the deck of the USS Randolph, shortly after being plucked out of the Atlantic Ocean. Photo Credit: NASA |

Grissom then performed some final checks, including some that involved the hatch system. In postflight briefing reports compiled in the book, Grissom stated in part:

I took the pins off both the top and bottom of the hatch to make sure the wires wouldn’t be in the way…I took the detonator cap off and put it toward my feet.

Again, Grissom’s action did not contribute to what was about to happen. According to Into That Silent Sea, this is what was supposed to happen: the rescue helicopter’s pilot, Jim Lewis, and his co-pilot were to sever the spacecraft’s whip antenna, hook a recovery cable onto the capsule, lift the capsule slightly to allow the astronaut to emerge, and lower a rescue sling. Grissom would then remove his helmet, wait for the hatch to blow on its own volition, exit the capsule, and put himself into the rescue sling. This setup had worked fine during Shepard’s spaceflight months earlier, minus one difference – the explosive-actuated hatch.

As Grissom waited for further instructions from the Hunt Club-1 rescue helicopter, the unthinkable happened as he lay back on his couch. The book stated, “Suddenly, he heard a dull thud as, without warning, the spacecraft hatch blew. He looked up in disbelief, not only seeing blue sky, but the unnerving sight of saltwater spilling over in the doorsill.” Grissom took off his helmet and exited the spacecraft, understandably in a state of shock, and soon was in a life-and-death struggle as he swam against the strong currents of the Atlantic, which would pose a challenge even for an Olympic swimmer.

|

| Enter Wally Schirra, who would vindicate Grissom in October 1962. 1960 NASA photo. |

Helicopter pilot Lewis and his co-pilot then attempted to hoist the capsule, but their efforts were futile, as their engine began to overheat due to its weight. A backup helicopter came in to save Grissom, who by now was in water coming over his head; he arguably was saved by a watertight neck dam that kept water out of his suit – his colleague and close friend, Wally Schirra, had recently persuaded him to wear it. (More on Schirra shortly.) After a short struggle, he was able to reach the rescue collar. While Grissom was thankfully safe and sound, the Liberty Bell 7 capsule was lost, only to be recovered from the bottom of the sea nearly 38 years later in July 1999.

An interesting coda to the Liberty Bell 7 story occurred during another Mercury mission. Over a year later, Wally Schirra flew the program’s flawless third orbital mission, Sigma 7, in October 1962. At the end of Schirra’s flight, he further vindicated Grissom’s story about the hatch blowing independently of any intervention. Burgess’ book, Liberty Bell 7: The Suborbital Mercury Flight of Virgil I. Grissom, discusses this at length, and also contains testimonies by fellow Mercury astronaut Donald K. “Deke” Slayton and NASA aeronautical engineer Sam Beddingfield that Grissom would have had a deep bone-bruise on his hand had he manually blown the hatch.

|

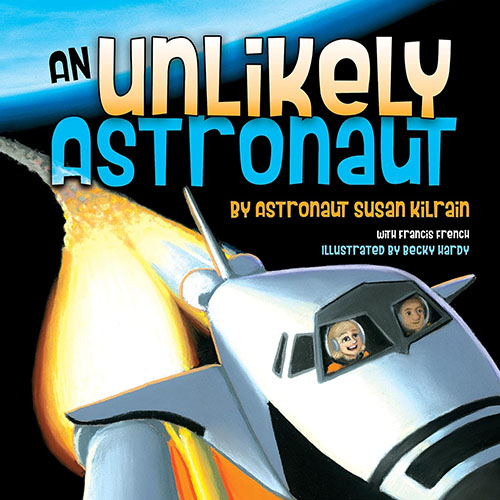

| Schirra sustained deep bruising and a cut to a hand after hitting the plunger meant to blow the hatch. Grissom suffered no such bruising. Photo Credit: NASA |

…But more on Schirra’s mission. At its end, according to Burgess’ book, Schirra blew Sigma 7’s hatch when he was ready to exit. The book underscored, “He had to hit the plunger with five or six pounds of fist force; so hard that he injured his hand. He was not slow to show the tell-tale impact bruising and cut on his hand at his medical briefing.” Schirra stated further in his own book, Schirra’s Space, that the brute force of hitting the plunger had cut through one of his metal-reinforced gloves. Slayton, Beddingfield, and Schirra all confirmed that Grissom had suffered no bruising of any type after his mission, thus nixing the theory that he somehow blew the hatch.

Gus Grissom should be remembered as one of the world’s spaceflight pioneers, not as some hapless “hatch blower” flailing in the ocean – because the latter suggestion never even happened.

Grissom would go on to have a resounding success once again with the first human-helmed Gemini mission, Gemini 3 (jokingly dubbed The Molly Brown, because this time, it would be “unsinkable”), in March 1965; co-piloted by then-rookie astronaut John W. Young, this mission was a vital sequential step in the Gemini program, which proved to be the critical bridge between Mercury and Apollo, making the Moon landings wholly possible.

His story, however, wouldn’t have a happy ending. On January 27, 1967, his life – as well as the lives of astronauts Edward H. White, II and Roger B. Chaffee – would be cut obscenely short by the Apollo 1 capsule fire. This time, an over-complicated hatch system – one that wouldn’t open quickly enough – would seal his fate.

Sources:

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.

31 thoughts on “Space Myths Busted: Gus Grissom Didn’t Blow The Hatch on Liberty Bell 7”

I’m so glad I’ve found and read abt this story and how tragic the film the right stuff got it so wrong. My only question is this – why has it taken so long to explain the truth abt the liberty bell incident

The Movie, The Right Stuff, was made in 1983. At that time NASA did not have proof that the Capsule Hatch blowing off on its own, so the script had to use the information that was known then. It wasn’t until much later, when the capsule was found, recovered, and examined that they were finally able to Confirm what Gus Grissom said when it happened. A glitch on the hatch caused it to blow off prematurely, and he had nothing to do with it.

Mary, not sure you read the article. Gus was vindicated in 1962 when another astronaut manually blew the hatch and had severe bruising because of the force it takes.

If NASA thought he’d blow the hatch they’d never have put him back in space.

I just hope the new Disney version of the right stuff gets it right!!! Gus didn’t deserve this stain on his record.

The Disney version does not portray the Astronauts in any good light. They are very loose with facts (example: conducting major capsule testing in the Hotel pool).

The movie “The Right Stuff” was a sensationalized cartoon of a motion picture about America’s Mercury program, full of glaring half truths and misinformation, that sacrificed Grissom’s legacy on the alter of cheap sensationalism.

That he was dead, that he might possibly be entitled to the benefit of the doubt they only paid lip service to in order to make him look like he had something to hide, had never crossed their minds. Controversy was the easier play here. It was built in. It simply played better. It sold tickets.

Grissom was an American hero who laid his life on the line many times before, and after that fateful day, and history ultimately vindicated him. I seriously wonder if the director of that silly movie, and his cadre of gag writers who worked so hard to portray him as a two dimensional weasel would have had the balls to sit atop one of those fire breathing missiles just one time.

You clowns owe his family, and his memory and a profound apology. If it were a sequel I’d call it, “The Right Thing.”

Very well said.,.

The movie is very disrespectful.

Just watching the movie again (after many times), the only difference is now I’m watching it with my 17 year old boy who is a space / aviation enthusiast.

I set the record straight. Gus was and will always be a hero.

Yeah what he said,

IN GUS WE TRUST

Outstanding response! That movie WAS a cartoon and how ignoble were all those involved in undertaking to smear the life of a great man. Only a coward would attack a dead man. It’s shameful and the family of Gus Grissom should have sued for slander.

Thanks for this clarification. Watching Right Stuff now and wondered about the truth.

The Right Stuff was inaccurate about Chuck Yeager as well. The scene where he takes the jet out and pulls high for an altitude record, and the engine flames out? He was one of several pilots flying those missions to test thruster nozzles mounted to the jet as it neared the edge of space. He had been warned several times that he was flying at too steep an attack angle to gain altitude, and that’s what caused the flame-out.

Why wasn’t Yeager part of the Mercury 7?

Because he didn’t have the required college degree.

I appreciate this article greatly, as Gus Grissom a great American hero does not deserve to have his reputation soiled.

Excellent article!

In reading Jay Barbree’s book on Neil Armstrong he makes the same statement, along with an earlier remark about Tom Wolfe and his book “What else could you expect written by one who never got closer to spaceflight than a Manhattan penthouse”.

Thank you Ms Carney for writing this to help set the record straight. It is so sad that Mr Grissom perished along with the crew of Apollo 1 in another bureaucratic snafu not only with the hatch but a combination of electricity and a pure oxygen atmosphere (What could go wrong!?). To have a book written after his death with any derision of his character is slanderous, my God, there was no one of any standing that would have even corroborated that nonsense, you would think that an author would take a bit of time to see if there is any proof before publishing. The family deserves a better memory of there great man. If anyone slandered my late father like this I could not imagine my anger and frustration.

His and his crew’s death on the launchpad during a test did serve a wonderful result though, it brought NASA up short and every system was vetted and changed so that no fire ever again has occurred in the crew quarters. Apollo 8 (electric short in the oxygen tank of the CSM when the motor to stir the tanks was actuated) and Challenger (O-ring seal on the fuel cell) both suffered from errors in the engine compartments.

(The Challenger disaster by the way lead to all future crews needing to wear life vests as it was found at autopsy that the crew had water in their lungs, so they likely drowned after being thrown clear during the explosion. My brother was involved with Mustang flotation at the time and was involved in quoting on that life vest project.)

I would never question anybody who knows more about spaceflight than I do (which probably is just about anybody), however… wouldn’t whatever was left of the Challenger astronauts when they hit the water- assuming their lungs were part of the remains- have filled with water , regardless of their “dead or alive” condition? I am not trying to be irreverent- just asking a question based on the comment to which I am replying. RIP to the Challenger crew…

“Apollo 8 (electric short in the oxygen tank of the CSM when the motor to stir the tanks was actuated)”

Was it not Apollo 13 that had the oxygen tank failure?

Otherwise, interesting and great article.

What I cant figure out is why the hatch wasn’t blown from inside of the capsule when the fire started. I know it happened fast. Under 30 seconds, but as far as I know, the capsule still had an emergency system in place. Overly complicated or not, couldn’t they have blown the hatch from the inside? And if not, wouldn’t the heat from the fir have detonated the explosive bolts on the hatch? The fire was hot enough, and the internal pressure high enough that it eventually breached the hatch as I recall reading, why didn’t the bolts blow?

The Apollo hatch did not have explosive bolts. The fire position also blocked their ability to even start opening the inner door that opened inward.

The hatch had a ratchet mechanism which required 90 seconds to open. It also opened inward; the air pressure made it impossible to open and actually caused the cabin to rupture. The boost protective cover also had a hatch that would have had to be opened. The astronauts never had a chance.

The fact is that if they ever really believed he was responsible, he would have quietly retired from NASA. He’d never had flown Gemini and wouldn’t have been tragically killed in Apollo 1.

More than the hatch, I think the REAL question from “The Right Stuff” was if Grissom actually carried a bunch of toy Liberty Bells up with him into space. The movie possibly infers this partially led to him having a hard time keeping his head above the water (although the rotor wash seemed to be the real issue)because there were a bunch of toys in his suit weighing him down. Did Grissom take the toys with him? Was he given the cold shoulder both on the carrier and back at NASA? Whats the real story there?

In the book “We Seven” which was written by the astronauts themselves, Grissom talks about all the trinkets that he carried to give to his friend’s kids. He lamented having them in his leg pockets and how he felt it was dragging him down in the water. He also recognized that he forgot to close the air hose inlet valve which allowed water to slowly come into the suit and drag him down nearly drowning him.

Great book if you love the space program.

In a video by the KC museum that restored the Liberty Bell 7, they did find over 40 mercury dimes in the capsule, as well as some $1 bills which were rolled tightly in shrink wrap and tied to wire harnesses by technicians.

Yes, he did have some coins, and toy capsules with him during the mission, but they were not in his suit at the time that he landed. They were found still in the capsule when it was recovered in 1999

Thanks for posting this and putting the record straight. Gus Grissom was a great astronaut and should remembered as such.

I’m English but Gus was my hero. His exploits in Mercury and Gemini were plastered all over my walls at school. I did not for one moment think he blew the hatch. I also don’t remember him floundering around trying to get hold of and climb into the recovery gear. His death, and White and Chaffee, in Apollo 1 was a shattering blow to anyone interested in spaceflight. I stopped watching Apollo stuff until the moon landing. Go Gus!

Gus Grissom is an American Icon. He deserves all the respect and privilege associated with it. By all accounts he was a damn good stick. I won’t even justify the sad sack bag of crap Hollywood that portrayed him in the “Right Stuff “.

It’s undeniable that NASA and the public thought he blew the hatch, hence the fact he didn’t get a ticker tape parade! I’m inclined to believe this is a possible explanation but not necessarily correct.

Spaceflight and exploration is incredibly complex and dangerous. It requires the combined efforts of many skilled engineers and technicians in addition to the astronauts who are ultimately at the greatest risk of any failure(s), those being life & limb. There would need to have been tremendous amounts of trust & respect for each other amongst the members of this community. I have always been bemused by the fact that Grissom’s immediate contact(s) within NASA, and NASA as a whole didn’t believe him when he said that he didn’t blow the hatch. I don’t think an individual such as he would lie to save face – I believe(d) him and always have . . .

Grissom and hatch blowing are far from all that the book, The Right Stuff, got wrong. In the NF-104A crash Yeager made at least four major errors — he caused the crash, he wasn’t a victim of anything beyond his control. Also, he was picked up by an H-21 rescue helicopter and flown directly to the hospital — not a farmer in a pickup truck who drove him to his office.

Two personal contacts destroyed my previously high opinion of Yeager. One comment by Scott Crossfield, crediting Yearer for recovering the Bell X-1B from an uncontrollable supersonic tumble led me to rate Crossfield as the finest gentleman I ever met. Years later I asked Yeager what he did to get the X-1B out its tumble and into a recoverable inverted spin. Yeager said “I didn’t do anything, it just came out that way.”