OPINION by Dale Skran, NSS Executive Vice President

On October 10th, 2018, the Air Force announced the funding recipients for National Security Space Launch program, the new name for the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program. Currently the EELV program supports two “commercial” launchers, the Atlas V and the Delta IV. However, the EELV program has become unsustainable due to the high costs of the Delta IV and the usage of Russian RD-180 engines by the Atlas V. To the shock of many, SpaceX was not one of the companies receiving funding.

So, what up with that? The issue is not a lack of commitment on the part of the Air Force to using commercial vehicles in the EELV/NSSL program. The Air Force long ago gave up building “Air Force” brand rockets. Nor is the issue some technical failing on the part of SpaceX—the Air Force has used SpaceX to launch both a GPS satellite and the X37B. The fundamental issue is not the weakness of SpaceX, but its strength. SpaceX has gone from being the “new kid” on the block to the dominant U.S. launch company, with 21 total launches in 2018 alone. Since the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the other provider certified to launch EELV payloads along with SpaceX, is moving from the Atlas V/Delta IV to the all-new, untested Vulcan, in reality soon SpaceX will be the only certified EELV provider with a reliable vehicle.

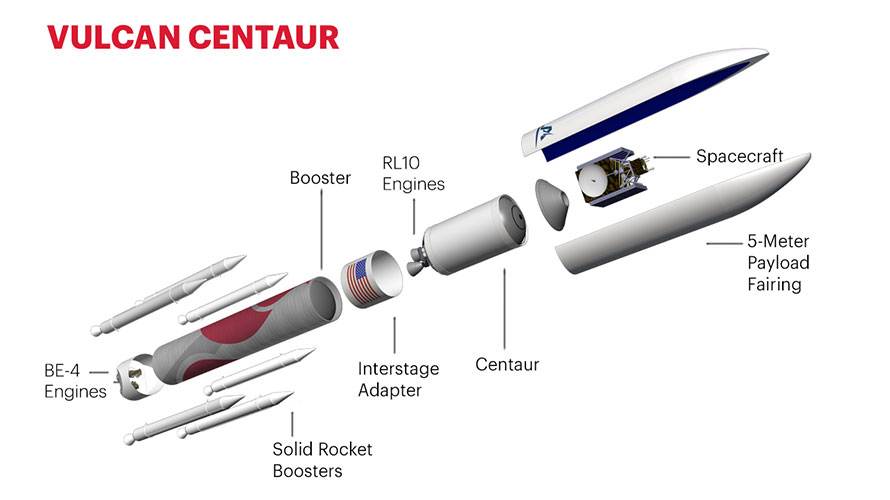

Thus, the central goal of the Air Force in the NSSL program is to ensure that there is at least one viable competitor for SpaceX. The obvious choice for this role is ULA with its strong engineering team, knowledge of Air Force requirements, and quality-focused culture. Alas, since the Vulcan is an all-new rocket using the all-new methane-lox BE4 engine provided by Blue Origin, there is a non-zero risk that ULA will not be able to deliver the same reliable service it has in the past. To help ULA along, the Air Force granted it $967M.

But suppose ULA fails with the Vulcan? The obvious way to hedge the Air Force’s bet on the Vulcan is a grant of $500M to Blue Origin to bring the New Glenn to operational status. The New Glenn is just as capable as Vulcan, targeted for full first stage reusability, and backed by Jeff Bezo’s billions.

Blue Origin New Glenn rocket

Blue Origin New Glenn rocket

What’s the fly in the ointment? Both the Vulcan and New Glenn use the same BE4 methane-lox engines for their first stages. There is another non-zero risk that despite vast promise, the methane-lox BE4 may not work out as hoped. To back-stop methane-lox the Air Force dropped $792M million on the Northup Grumman [former Orbital ATK] mostly solid-fueled OmegA rocket. This final investment by the Air Force serves two purposes: another level of redundancy in NSSL, and a subsidy to the solid-rocket industry that supports ICBM development. It is also worth noting that an investment in the SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship would not protect against systemic flaws in methane/lox engines, since SpaceX is building its future on the methane/lox Raptor engine.

Northrup Grumman OmegaA rocket.

Where does this leave SpaceX? More or less assured of a place as one of the two winners in the NSSL program. The Falcon 9 is already reliable, and getting more so all the time. The Falcon Heavy seems on a course to be nearly as reliable two years hence as the F9 is now. The Falcon 9 Block 5 technology has already demonstrated three flights of the same first stage, with more to come.

The battle for the second slot between ULA and Blue Origin will be awesome. For ULA, this is do or die. Blue, however, already has a backlog of commercial contracts for New Glenn, and promises to be strong competition for ULA. On Jan 31st, 2019, Blue announced that it had won a contract to launch an entire LEO datasat constellation for Telesat, with options ranging from 192 to 512 satellites. The ULA plan of re-using only the first stage engines but the entire second stage in space is intriguing. Equally intriguing is the New Glenn’s 7-meter fairing, promised first stage reusability, and potential 2nd stage reusability.

There remain two questions of interest. First—will the Air Force stick to its current plan of selecting only two providers, if both ULA and Blue are equally strong? Second—how will the 800 pound gorilla in the back room, the SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship, effect things?

The first question is imponderable, but the second is the more interesting. When 2022 rolls around, and the Air Force is ready to select the winners of NSSL, what will happen if they look out the window and see Super Heavy/Starship providing regular service to LEO/GEO, as well as launching to the Moon and Mars?

Reliability has always been the ace in the hole for ULA, but Vulcan is a new deck of cards. We could see a situation where 2023 rolls around, and both New Glenn and Super Heavy/Starship are in routine operation, launching 12 or more times annually, while Vulcan starts at zero and never comes anywhere close to catching up.

This is going to be interesting.

2 thoughts on “Thinking about EELV Phase II funding and why SpaceX was left out of it”

With all due respect…. hogwash. The F9Heavy barely qualifies against most of this group.

Also ULA gets the greatest award for the least ambitious new rocket (no reusability until 2025…. then partial only. Starship/SH is Fully reusable and therefore the only option that allows SH lift, large volume and Full reusability…. but That’s not worth funding and Spacex has to go through lay-offs to fund their own projects.

Recall the Only funding Spacex got from AF for FH was 60m for engine development when they wanted to award (1.5-2x that to ULA for BE-4/Rocketdyne) (They needed it to replace RD-180, Spacex didn’t ask for it, but it would have been strange to only award it to ULA.

The clear motivation has always been to prop up ULA vs Spacex. ULA’s competitors (but not its most dangerous one) receive funding (less funding for more ambitious projects for no good reason) so that AF can give ULA another handout with the cloak of promoting “competition”.

This is simply an extension of the SLS pork project pushed by politicians to prop up ULA/Boeing.

If I’m wrong, then Please explain to me the logic of funding ULA at 1.5x the dollar value as Blue Origin or any of the others (again with $0 going to the team with the most need for dollars for the most ambitious project). Explain to me why $250m of ULA’s excess funding (beyond all others) couldn’t have gone to Starship/SH..The Starship/SH is vastly superior to the competition in every respect but is strapped for cash. Also the Raptor engine is entirely different (Full Flow Me/O2) vs (Staged Combustion/O2). They are not the same risk at all. Also Spacex will have to win 12 or more flights to earn the $500m of the smallest award… some few years down the road at least… hardly equitible. So future earnings don’t help them when they need the cash for Starship/SH now. Also note that unlike all the other competition, Spacex is the only one that can place 100t of cargo on the moon or an 8m diameter payload… .or 50-100 workers on the moon in one flight.

The AF has a long and jaded history of corruption in acquisitions. Constantly botching or blatantly rigging competitions… Tanker competition – rigged…twice (Boeing caught in bribe 2nd time around). F-22 – Boeing’s F-23 got wrong range specs and they got stuck with an air superiority Tanker-fighter because competitor knew to ignore outrageous range requirement. General that awarded 36 rocket order weeks before Spacex was eligible to bid… then takes VP job with ULA contractor…. Only 129 F-22 built vs the 750 planned because AF couldn’t figure out what they wanted instead of traditional Block builds and…. amazing “cost plus” contracts. The B-1A….oops B-1B project that only built 100/500 bombers… breath-takingly expensive B2. So the bulk of the USAF is F-15 (designed 1972), F-16 (designed 1974), B-52 (designed during the late Jurassic). No new ICBM since the MX Also ran into breath taking cost overruns and only replaced 100 missiles with Minute Man missles (designed 196x?) still the bulk of service.

With a long tradition of corruption and hair-pulling failure…. why would anyone believe the warped logic that “spacex doesn’t need the money”…. but all of the others do

Hard to argue with that long and sordid tale of institutional corruption and MIC business as usual.

I think all your concerns are valid, but unlike you I am a bit more optimistic about SpaceX’s chances… I think they can pull it off without government help, and there are substantial speed/nimbleness advantages from not having it.

I might be wrong, but let’s hope not. We need SpaceX.