This Space Available

By Emily Carney

Two new books illuminate the challenging times two NASA Group Five astronauts experienced during the 1970s, a decade more known for delays in human spaceflight than actual human spaceflight. Wonders All Around: The Incredible Story of Astronaut Bruce McCandless II and the First Untethered Flight in Space reveals the unexpected, quirky side of the astronaut most popularly known for being “The Poster” on countless kids’ walls far beyond 1984’s STS-41B, while Al Worden and Francis French’s The Light of Earth: Reflections on a Life in Space fills in gaps left unanswered by 2011’s classic Falling to Earth – and also wraps up a life well lived. In these books, we learn of the frustration McCandless felt being publicly portrayed as “The Forgotten Astronaut” of the 1966 astronaut group, and of Worden’s feeling of resignation tinged with rage after a scandal all but destroyed his promising career. Note: book spoilers ahead.

Wonders All Around, written with a poetic, dreamlike spirit by Bruce McCandless III (you may have guessed it, but the writer is the elder McCandless’ son), begins with a tense family car trip during the Bicentennial year, with Bruce II driving the legal 55 mph speed limit to not only conserve gasoline, but to also avoid getting a traffic ticket, or possibly arrested. By this point, Bruce II was out of the running for any Apollo flights, because that program had ended during the previous year. But he was all too conscious that the press was looking for a reason why he hadn’t yet flown in space, unlike many of his colleagues (including Worden). McCandless III writes, “Some men would have started looking elsewhere for a job. My dad’s reaction was just the opposite. He kept pushing for a spot on some future spaceflight, even if the flight was, at this point, largely hypothetical. He worked hard. He checked all the boxes.” And he could only drive 55.

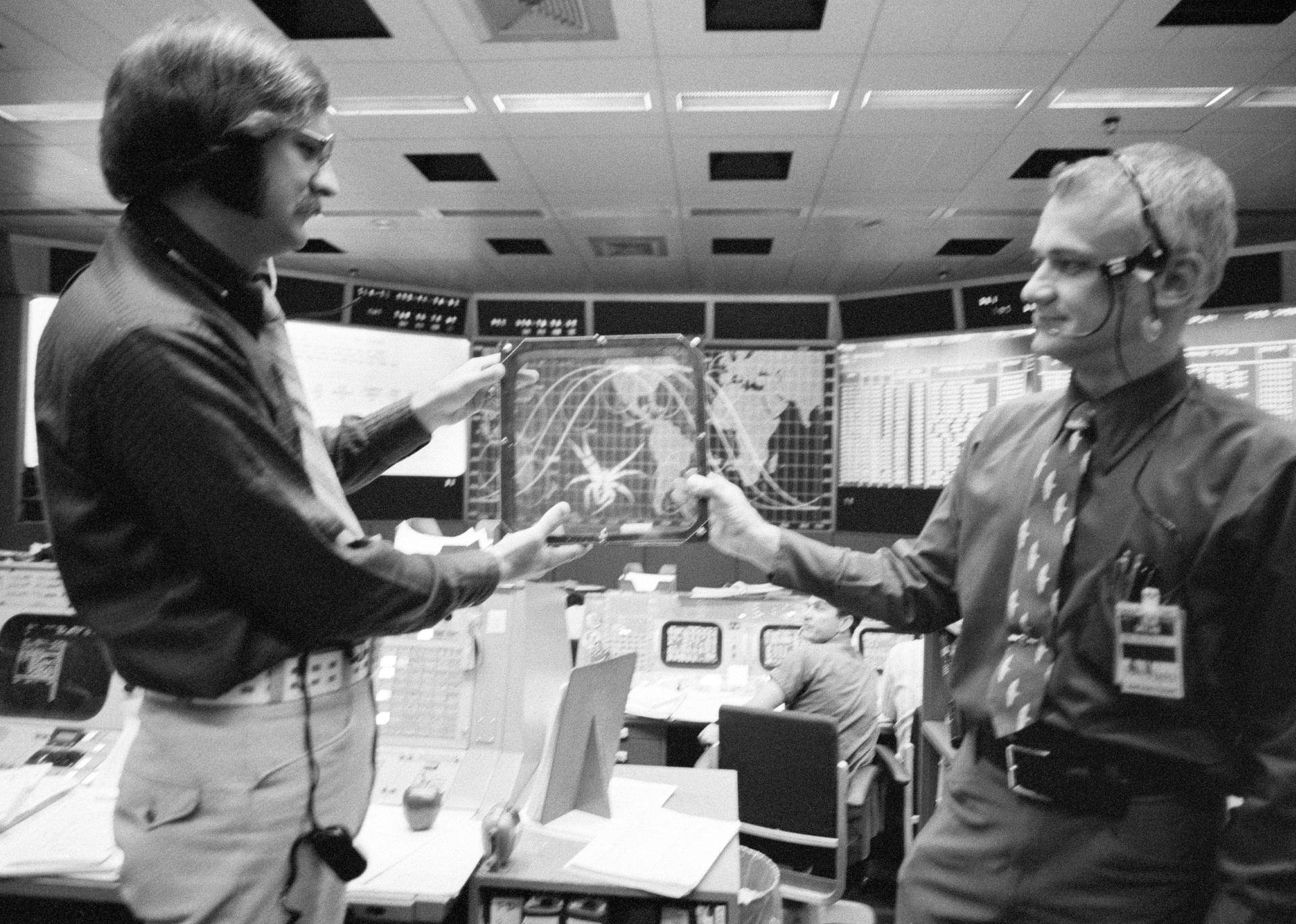

The same chapter discusses a cruel newspaper article published in 1973 that emphasized that McCandless II was one of the only astronauts from his group not to be selected for an Apollo or Skylab mission, and even went as far as calling him “the forgotten astronaut.” In fact, the article – written by William Stockton for Rocky Mountain News, and published on November 23, 1973 – is entitled “Skylab Communicator is Forgotten Astronaut.” McCandless III states in the book’s notes that his father had in his possession not one, but five copies of the article, which had been distributed nationwide via the Associated Press. The heartbreaking mental image of the elder McCandless at age 36, slumping in anguish at the family dinner table at the savagery of this article, underscores the very real mental toll the space program took on its astronauts, who were feted as macho, perennial fliers.

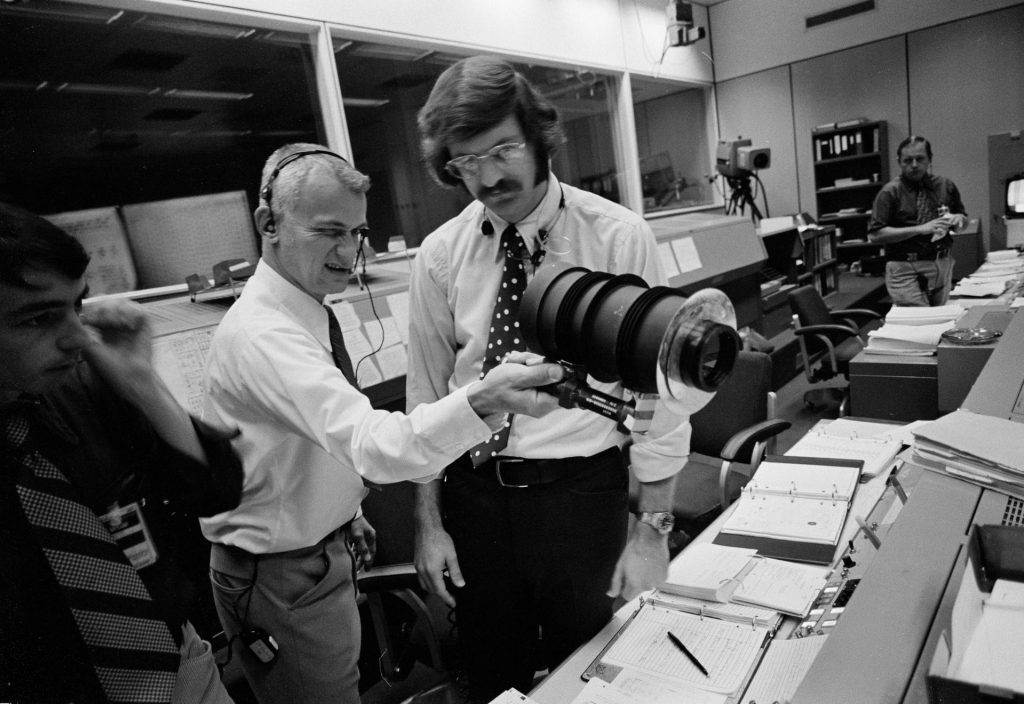

But McCandless II was different: he displayed more of a scientific aptitude than his pilot colleagues, loved rehabilitating birds, was a member of the Audubon Society, was less boisterous, and more thoughtful. He preferred a Volvo to a lipstick red Corvette. The newspaper article failed to mention at length McCandless’ contributions to the Apollo and Skylab programs, as well. People opening up their newspapers on November 23, 1973 didn’t read about McCandless being one of the most identifiable voices during Apollo 11, helping to save Skylab after the space station had suffered crippling injuries on ascent, or his role pioneering a Buck Rogers-esque flying machine that was tested in Skylab’s spacious orbital workshop. But those success stories probably wouldn’t have sold as many papers.

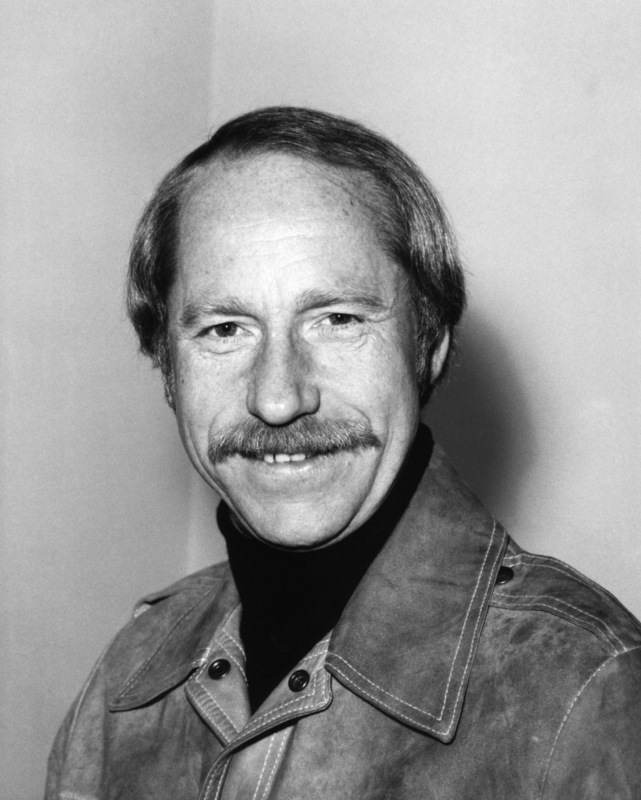

As we saw in Buzz Aldrin’s 1973 memoir Return to Earth and Worden’s Falling to Earth, the pressures were a lot even for the astronauts who flew. Al Worden would become the victim of a newspaper article himself in 1972, months after returning from the super-successful Apollo 15 lunar mission. The Houston Chronicle would publish a damning front-page article dissecting the stamp scandal that tainted the crew’s reputations, and the newspaper even put a black border around the crew’s photos. Worden never forgot the calumny, and discusses the aftermath of that terrible time in The Light of Earth.

While Worden was “allowed” to stay at NASA – sent to a sort of exile at NASA Ames, far away from Houston, Astronaut Central – he was well aware he, in his words, “was really just riding out the storm there.” In 1975, he left NASA and the U.S. Air Force “knowing I did not want to go work for a big company. As a matter of fact, feeling kind of tainted from the end of my NASA career, I wasn’t sure any big company would want me on board anyway. So I never really tried.” Worden did perhaps one of the most un-astronaut things someone could do in 1975: he took the show on the road. “…I loaded all my belongings into a motor home and hitched my sports car to the back of it. I headed east and went back to school. Living in a motor home in winter is cold, but I made it work. Life wasn’t going to keep me down for long.” Worden traded his flight suits for bell bottoms and longer hair, and thus began his bohemian years in California. We also find out that while Worden was not a big fan of the space shuttle’s design, if he’d been given the chance, he still would have been glad to fly it during the 1980s. (The door is now open for Worden and McCandless space shuttle alternate histories.)

Life didn’t keep Worden – or McCandless – down for long. Worden would start a string of successful businesses, and his later years found him having one of the most spectacular public returns to the spotlight perhaps of any Apollo-era astronaut, after the publication of the validating Falling to Earth. And McCandless would fly on two legendary space shuttle missions, becoming the first “human satellite” on STS-41B, and deploying the Hubble Space Telescope on STS-31. Perhaps most interestingly, Wonders All Around also chronicles McCandless III’s life growing up with his dad, and answers many of the questions those have thought about what it must like to be a famous astronaut’s child: did you see him the same way as everyone else did? What did you know about him that others didn’t?

The Light of Earth shows an Al Worden who had made peace with his tumultuous past, and was optimistically looking forward to the future, until his life was cut short in March 2020 at age 88 (note: despite his age, he wasn’t done yet…not even close). Wonders All Around has a similar theme, and depicts McCandless II as being unstoppable despite becoming increasingly frail prior to his December 2017 passing. A common refrain that runs through Wonders All Around is one of the elder McCandless’ favorite sayings: “Onward.” This word could apply to both McCandless and Worden, who both relentlessly looked to the future with hope even during their dark nights of the soul.

Wonders All Around is available for purchase via Bruce McCandless III’s website; The Light of Earth is available for purchase via the University of Nebraska Press’ website.

Featured Photo Credit: “Astronaut Bruce McCandless II, left, shows off a mock-up of the occulting disc for the T025 Coronagraph Contamination Measurement Engineering and Technology Experiment to be used by the crewmen of the third manned Skylab mission (Skylab 4), now into their eighth day in Earth orbit. On the right is flight director Neil B. Hutchinson. The men are in the Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) of the Mission Control Center (MCC) at Johnson Space Center. Photo credit: NASA.” This photo is dated November 23, 1973, the same day a newspaper article depicting McCandless as “NASA’s Forgotten Astronaut” was distributed nationally via the Associated Press.

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.