This Space Available

By Emily Carney

During the last year, This Space Available focused upon – and will continue to add to – the parallel, then wildly divergent stories of Brian O’Leary and Gerard K. O’Neill, two working scientists who, while both having brushes with NASA, found their careers and lives defined by their work done largely outside of the space agency. O’Leary, an astronomer, had been selected to be part of the 1967 “Excess Eleven” scientist-astronaut group, but resigned when he infamously found that flying T-38s wasn’t “my cup of tea.” O’Neill, a nuclear physicist and who, at 40, was mid-career in 1967, was a finalist for this group, but didn’t quite make the cut.

However, this may have been for the best, because the Excess Eleven group would see many of its members resign before Skylab even made it off the ground in May 1973. One of the astronauts who left this exclusive cadre was physicist Dr. Philip Chapman, who was NASA’s first Australian-born astronaut.* This is his story, and as you will see, many of the frustrations that resulted in his 1972 resignation from NASA were echoed by former colleague O’Leary in his 1970 opus, The Making of an Ex-Astronaut.

Prior to his mid-1967 selection, Chapman, at 32, had already enjoyed a life worthy of a standalone doorstop biography, having been a pilot in the Royal Australian Air Force Reserve (he, unlike O’Leary, definitely found flying to be his “cup of tea”), an Antarctic explorer studying the continent’s aurorae at age 23, and having earned a post-graduate education through Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He completed the necessary steps to become an American citizen in order to gain eligibility for the 1967 astronaut group, and undoubtedly his diverse life and career experiences contributed to his selection. Many space enthusiasts first “met” Chapman within the pages of the aforementioned book. O’Leary, in a chapter simply entitled “The Excess Eleven,” introduces the reader to each of his colleagues, starting alphabetically with Joe Allen. He then describes Chapman, who he incorrectly states is 35 during this time; perhaps Chapman’s sophistication made him seem older to O’Leary, who then was 27, and only recently had completed his post-graduate education.

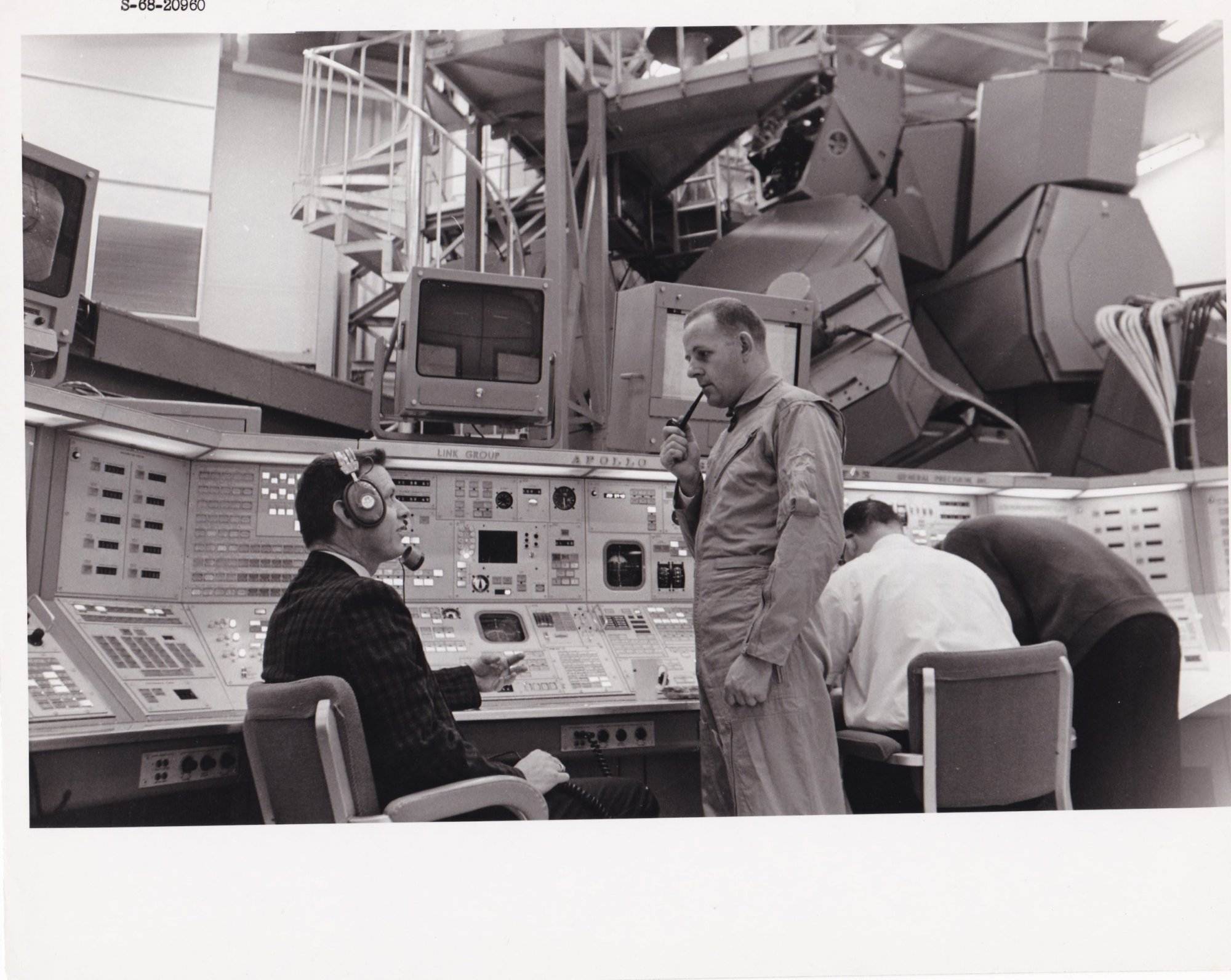

O’Leary wrote, “It always struck me as interesting that he had spent time in the Antarctic, because he physically reminds me of a penguin. I don’t know why, exactly. Perhaps it is the combination of a balding head, a large nose, and a deft but slightly waddling walk. When he is not talking, he smokes a pipe with a very reserved, deadpan Australian face, like a limp pancake.” (Indeed, an ABC News clip from 1969 shows Chapman smoking his trademark pipe, replete with an almost hilariously deadpan facial expression.) Limp pancakes aside, O’Leary conceded that when his colleague was interested in something, his demeanor completely changed: “But when [Chapman] talks there is a dramatic transformation: his face comes to life and you can almost see his brain waves light up his scalp.” Described by his younger colleague as “imaginative and futuristic,” O’Leary added that Chapman “is very philosophical and you could talk to him for hours about almost anything and he’d have something interesting to contribute.”

Notably, O’Leary also depicted Chapman as the group’s de facto leader: “He was also the most courageous spokesman of the group. Whenever we had a griping session about pay, the Time-Life contract, university affiliations, travel, etc., he would spearhead these discussions and would have no fear to report these gripes directly to [Alan] Shepard or [Deke] Slayton.” While the younger O’Leary clearly appreciated Chapman’s forthrightness with higher-ups, the higher-ups wouldn’t always appreciate Chapman’s forthrightness; as we will see, O’Leary foretold how Chapman’s Australian bluntness wasn’t always well-received by their pilot-astronaut colleagues.

Having already flown with the RAAF in his home country, Chapman took to the skies with ease. In the book NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts by Colin Burgess and David J. Shayler, he enthused, “I really loved flying jets, especially the T-38. It is an extraordinarily agile machine, and it needs a very light touch on the controls. If you push the stick hard over, it will complete an aileron roll in less than two seconds. My first few solos were quite scary, but it became very easy to fly once I was used to it.” While Chapman excelled at flying and successfully completed other astronaut training milestones, it was soon apparent that late 1960s budget cuts at NASA threatened his group’s chances of making it to space in the near future.

By the early 1970s, Apollos 18, 19, and 20 were canceled, and remaining missions were reshuffled in terms of landing sites and scientific priorities. The Apollo Applications Program would ultimately be whittled down to one Skylab space station with three visiting crews, and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. O’Leary, whose unease with flying coupled with a growing awareness of a lack of actual scientific opportunities within NASA’s human spaceflight program, saw the writing on the wall early and resigned in early 1968.

Deke Slayton, head of the astronaut office, acknowledged the divide between the scientist-astronauts and the old guard pilot-astronauts in his autobiography coauthored with Michael Cassutt, Deke! Slayton reported, “We had already been confronted with some public bitching by the scientist-astronauts, notably Phil Chapman of the new group, and Curt Michel from the 1965 selection. They realized they weren’t getting any time to do research and were spending it all traveling around the country learning what NASA did and sitting through lectures on the Apollo spacecraft. We let Michel go ahead and start spending most of his time at Rice University doing research. It was basically his first step out of the door.” Slayton’s thinly veiled annoyance with these two particular scientist-astronauts would foreshadow two events 1969 and 1970, respectively: Michel’s resignation from NASA, and Chapman’s turbulent time as Apollo 14’s mission scientist.

Fake Aliens, and the Beginning of the End

Even before Apollo 11 touched down upon Tranquility Base, Chapman intuited that public and political interest in spaceflight was flagging. But he and a few of his colleagues had an…interesting plan. He and a fellow group of astronauts seriously discussed sneaking Neil Armstrong goat urine, which was to be “discovered” upon the Moon’s surface (Chapman: “…[T]he chemists [back on Earth] would discover that somebody or something not of this Earth had taken a leak on the Moon.”). In Scientist-Astronauts, Chapman joked, “A few months before Apollo 11, I was sitting in a bar with a few other astronauts, when the conversation turned to what we could do if the USSR quit the space race. Somebody suggested that we should create a fake alien artifact, and give it to Neil Armstrong to ‘find’ on the Moon…of course, this was a joke – almost – and we never did anything about it. I rather wish we had: we might now be much farther ahead in space.”

him is George Prude Jr. from the Simulation Branch, Flight Crew Support

Division.” Photo and caption supplied by Colin Burgess.

By 1970, Chapman had a plum assignment as mission scientist for Apollo 14, which would launch in late January 1971. A short interview from around this time is available on YouTube, and he certainly looked like the archetypal Apollo astronaut as he chatted amiably with a beehived woman reporter, Australian accent notwithstanding. However, while by all appearances he looked to be advancing quickly up the astronaut ladder, he butted heads frequently with Slayton. In Scientist-Astronauts and Burgess’ Shattered Dreams, which was published last year as part of the University of Nebraska’s Outward Odyssey series, Chapman was very vocal about his dissatisfaction with Slayton’s leadership of his astronauts.

In Scientist-Astronauts, Chapman held nothing back: “To put it plainly, it seemed to me that Deke had no understanding that leadership is a two-way street, and no vision of spaceflight beyond keeping it as his own little fiefdom. Furthermore, he apparently thought that the only legitimate purpose of a space mission was flight testing a vehicle; that science in space was a worthless distraction, and that scientists were inherently unacceptable as astronauts, regardless of their flying skills.” To be fair, Chapman wasn’t the first astronaut or spaceflight personality to disagree with Slayton’s decisions around this time period (for example, his decision to let Alan Shepard command Apollo 14 has been criticized by some as Mercury 7 cronyism).

During this time, Chapman would face more opposition from Slayton when he tried to design scientific duties for astronaut Stuart Roosa, Apollo 14’s command module pilot. According to Chapman, Roosa approached him asking for a list of more scientific tasks he could undertake while he orbited the Moon during his crewmates’ EVAs. Chapman suggested an attempt to image Kordelewski clouds (faint clouds believed to exist at Lagrangian points L4 and L5); he stated, “All [Roosa] had to do was to point a camera in the right direction at the right time, and he might make a major scientific discovery.” However, Slayton was not happy with this idea, and Chapman reported, “he carpeted Stu and me.” While Chapman argued that focusing on formal experiments left Roosa ample spare time in which he could undertake meaningful scientific work, Slayton was unmoved, and even stated rather punitively that Roosa would be removed from the flight and banned from other flights if he did impromptu experiments.

Slayton soon found another hill to die upon: according to Chapman, he sent a memo to all astronauts stating that TV reporters judged a mission’s success by its number of completed objectives. It became painfully obvious to Chapman that by limiting scientific objectives, the number of overall objectives was smaller and more achievable, signifying “mission success” to the media. Here, Chapman’s Australian “insubordination” (his word) would surface again: “I was dumbfounded by the idea that the way to increase interest in spaceflight was to minimize the useful results…I told Deke what I thought of his new policy.” Ironically, the same outspokenness and boldness that had likely impressed the astronaut selection board in 1967 – and his astronaut group colleagues, including O’Leary – now seemed to work against him. And within 18 months, the cancellation of a space station that held promise for Chapman would spell what he viewed as the death knell of his astronaut career.

Don’t miss the continuation of this appendix to This Space Available’s O’Leary/O’Neill saga, which will discuss the factors that led to Chapman’s 1972 resignation from NASA, and his ensuing career that actually had many parallels to O’Leary and O’Neill’s 1970s work.

Many thanks to space historian Colin Burgess for his assistance with research for this piece.

(*While Chapman was the first Australian-born astronaut selected, oceanographer Dr. Paul Scully-Power would become the first Australian-born scientist to fly in space, as he was a payload specialist aboard 1984’s STS-41G.)

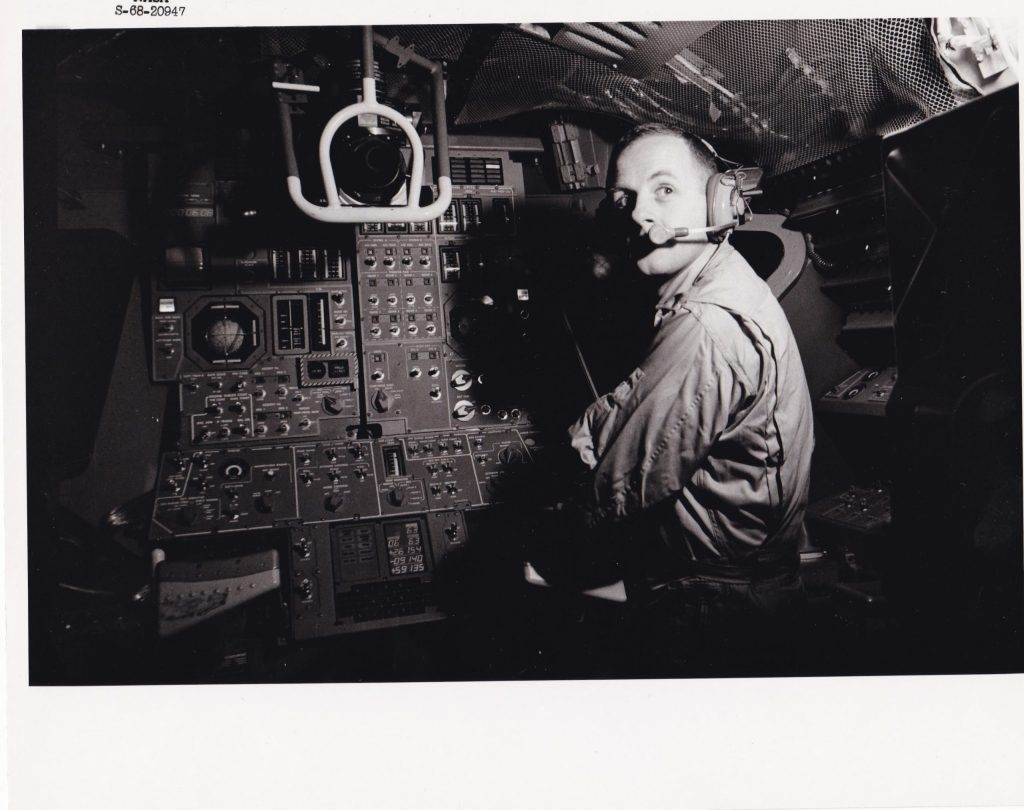

Featured Photo Credit: Dr. Philip Chapman inside the Lunar Module Mission Simulator at Houston’s Manned Spacecraft Center, 1968. Photo supplied by Colin Burgess.

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.

4 thoughts on “First Aussie: Dr. Philip Chapman, Apollo’s Astronaut from “Down Under,” Part One”

Too bad. Phil was a competent guy!

I really enjoyed writing this, and reading about him. Very outspoken guy, which of course I love.

A great insight. Thank you.

I always get the feeling that in the later stages of Apollo there was a real sense of Science vs Engineering-Operations. Not sure if I am just missing anything, but During the Shuttle era, there was ‘Plenty of science to go around’, and this wasn’t an issue? At the moment with Dragon & Starliner it seems like a dead issue as there is such an operational focus on just getting to the station. Will this issue pop up again or is NASA? Or Heaven forbid, Will NASA get really, really good at articulating their long term program and integrate scientific objectives with operational reality right from the get-go.